Research and teaching should be closely integrated, in any teaching and learning setting in higher education and we regard it as a core value that higher education students and their teachers are inspired by research. Research-based and inquiry-based learning bring this a step closer by requiring students to adopt an active, inquisitive attitude. Students are no longer merely observers; they become participants of research and learning. As a consequence, research is not just the basis of teaching, but is actually the very core of teaching and learning.

Not all students aspire a career in research, however it is important that all students have the opportunity to acquire sound skills in research methodologies and learn about the latest research insights. Furthermore, the inquiry skills that students gain can be applied to question, analyse and tackle the important challenges that our society is facing today (See also Transferable skills).

Objectives

- Students adopt an proactive, inquisitive attitude;

- Students learn to assess the value of different sources of information;

- Students are familiarised with the important research themes within their disciplines;

- Students learn to articulate critical research questions with appropriate academic standard;

- Researchers train students in the most important discipline-related research methods;

- Programmes stimulate the connection between different disciplines and demonstrate how different knowledge domains and approaches could enhance each other.

What are the key aspects?

Research-based and inquiry-based learning are approaches to integrate research into teaching and learning; they are closely related but have a different focus. Whilst research-based learning could be understood as involving students directly in current research projects, it is often employed to familiarise students with research and research methods in the context of their discipline. Inquiry-based learning could be understood as an approach to teaching and learning in which the student is stimulated to develop a proactive attitude to fact-finding and problem-solving, rather than depending on presented facts or established knowledge. Inquiry-based learning is often employed to explore societal issues or dilemmas and is usually applied in an interdisciplinary context. (See teaching examples below).

In this context there are roughly three options to research-based and inquiry-based learning to consider:

- Focus on research content or processes and problems;

- The students as audience or participants;

- Focus on disciplinary research or interdisciplinary (often societal) inquiries.

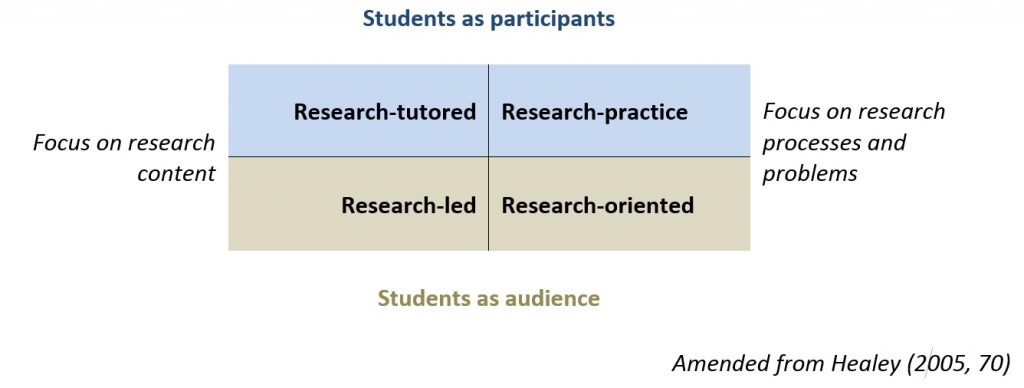

Approaches 1 and 2 are reflected in The Higher Education Academy (2005, 70) matrix that distinguishes four main ways of engaging undergraduates with research. It distinguishes clearly between students as participants and students as audience:

Students as participants

Research-practice

Here students are directly involved in research projects. This could vary from micro-research projects that can be completed in a day to major assignments or theses.

Research-tutored

By engaging students in discussions around current research topics, students learn to appreciate and recognise different vantage points in academic debates. This could be done, for example, through involving students in the organisation of seminars or through organising classroom debates.

Students as audience

Research-led

This involves teaching current research in the discipline. For example, by referring to current research in lectures and sharing up-to-date research-finding in reading materials.

Research-oriented

Here the focus is teaching students research skills and techniques. For example, through teaching about different research methodologies, including laboratory skills, writing papers and fieldwork.

It is important to note that the emphasis on the approaches described above to integrating research into teaching and learning should be seen as different strategies for students to acquire knowledge and skills as well as insight in research approaches. The production of valid research outcome is not necessarily the main objective. (see also Visser-Wijnveen, G. J. [2013])

What are important questions?

- What are options for strengthening the role of research in my teaching?

- How can I organise collaboration in teams of students?

- How could students be engaged in the department’s research? [to follow]

- What steps are involved in setting up a collaborative inquiry project? [to follow]

- How could we promote an active and inquisitive attitude in students? [to follow]

How do you know you are on the right track?

Making progress comprises (re-)designing education to meet your objectivesas well as keeping track of results. But how can you know that you are making progress? Summarizing the general process of educational design and specific models for curriculum re-design we propose the following three-step approach:

Step 1. Reformulate your objectives into questions concerning the current situation (today) and the desired situation in five years form now

Step 2. Make the answers to the questions measurable

Step 3. Use the answers as input for further (re-)design

For example:

- To what extent do students adopt a proactive, inquisitive attitude today and in the future? Examples of measurable answers: (%) students ask critical questions during lectures; (%) students initiate own research (projects)

- How do students learn to assess the value of different information sources today and in the future? Examples of measurable answers: by lectures/group work/assignments in (x) courses/minor

- How are students familiarised with the important research themes within their discipline today and in the futre? Examples of measurable answers: by observing and/or participating in (x) research projects in (x) lectures/courses/minor

- How are students trained in the most important discipline-related research-methods today and in the future? Examples of measurable answers: in (x) lectures/skills training/lab sessions/ demonstrations/ internships

- How do researchers support students in learning to articulate critical research questions with appropriate academic standard today and in the future? Examples of measurable answers: in (x) courses; in a module on research ethics; in supervision

- How do programmes demonstrate and stimulate the connection between different disciplines, knowledge domains and approaches today and in the future? Examples of measurable answers: by addressing societal issues/wicked problems in (x) lectures/ assignments/courses/minors/research projects

Further reading

- Jenkins, A., Healey, M. & Zetter, R. (2009) Developing undergraduate research and inquiry, [accessed July 2017] https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/developing-undergraduate-research-and-inquiry, York: The Higher Education Academy.

- This paper argues that all undergraduate students in all higher education institutions should experience learning through, and about, research and inquiry. It also describes 19 strategies to develop this agenda as well as case studies.

- Jenkins,A., Healey, M. & Zetter, R (2007) Linking teaching and research in disciplines and departments. York: The Higher Education Academy

- This chapter provides an overview of current challenges and knowledge about the integration of research and teaching in higher education.

- Van der Rijst, R. M. (2013) The transformative nature of research-based education: A thematic overview of the literature. In: Bastiaens, E., van Tilburg, J., & van Merriënboer, J. (Eds.), Research-based learning: Case studies from Maastricht University (pp. 3-21). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- This chapter provides examples of research with teaching and research in disciplines and department.

- Visser-Wijnveen, G. J. (2013) Vormen van de integratie van onderzoek en onderwijs [Forms of the integration of research and teaching]. In D. M. E. Griffoen, G. J. Visser-Wijnveen, & J. M. H. M. Willems (Eds.), Integratie van onderzoek in het hoger onderwijs: Effectieve inbedding van onderzoek in curricula (pp. 61-74). Groningen: Noordhoff Uitgevers.

- In this paper, the notion of integrating research into teaching and learning is explored in the context of knowledge development.

- Heron, J. and Reason, P., The practice of co-operative inquiry: research with rather than on people. [accessed July 2017] www.peterreason.eu/Papers/Handbook_Co-operative_Inquiry.pdf

- Minner, D.D., Levy, A.C., & Century, J. (2010) Inquiry-based science instruction – What is it and does it matter? Results from a research synthesis, 1984 to 2002. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 47, 474-496.

- Vereijken, M. W. C., van der Rijst, R. M., van Driel, J. H., & Dekker, F. W. (2017) Student learning outcomes, perceptions and beliefs in the context of strengthening research integration into the first year of medical school. Advances in Health Science Education.

- This paper describes the influence of a curriculum change aiming to strengthen the role of research in teaching about student learning outcomes and perceptions of research in teaching.

Example research-based learning (LUMC)

Academic Scientific Training at the LUMC

First-year undergraduates in Medicine

Lecturer: Prof. dr. F.W. Dekker

What is the teaching module about?

Epidemiology teachers have collaborated with primary care teachers in developing a first-year student research project. Students collect data about co-morbidity, medication, care dependency and cognition among three patients during an early clinical experience in nursing homes, right at the start of the students’ medical education in September. Students enter their data into an online database in order to establish a large dataset (300 x 3 = 900 patients). In December, the students return to the nursing homes for one day to repeat their data collection and to come up with their individual research questions ‘at the bedside’. In the new two-week course after this, basic knowledge and skills were taught to enable the students to answer their own research question. In two small group sessions, students have practiced formulating a research question and have learned to understand the structure of a research paper. Students had a few lectures on epidemiology, basic statistics and practice in simple data analysis. Then students spent two days analysing their data and answering their own research question. They wrote a two-page research report and presented their findings to their peers in a small group session. All students were actively involved as participants in research, doing their own research project as a learning activity (also see Vereijken et al. 2017).

What are the objectives?

- Students have a lived experience, which contributes to their understanding of what it means to create medical knowledge in a real clinical setting

- Students learn to reproduce parts of the research process, in particular the collection of patient data

- Students learn to formulate a research question, to conduct statistical data analysis and to present research findings

Example inquiry-based learning (Governance and Global Affairs)

Module Complex Societal Challenges

(Minor: Innovation, Co-Creation and Global Impact)

Location: Campus The Hague

Lecturers:. T. Baar MA, Dr H.Sjerps

What is the module about?

This interdisciplinary module asks students to tackle wicked problems and strategically work towards solutions. Working together in small multi-disciplinary teams, they analyse a local sustainability challenge and propose a social Innovation that could serve as a solution to a problem. As part of the assignment they need to collaborate with stakeholders in order to challenge assumptions about the societal challenge and research the stakeholders’ needs that are related to the challenge.

What are the objectives?

Students learn to

- work constructively in multi-disciplinary teams;

- distinguish between different approaches of action research;

- try-out collaborative inquiry research approaches in real life situations, and;

- apply collaborative inquiry research in their own responsible innovation projects.

This way they learn to take up different perspectives, explore cross-disciplinary boundaries and practice research skills.